BY SADAF SULEMAN

BY SADAF SULEMAN

The building has survived empires, migrations, and decades of urban transformation, yet the threats it faces today are unprecedented.

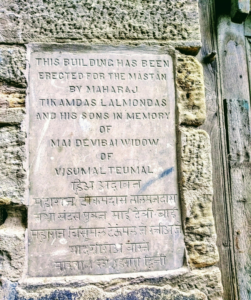

A faint inscription on the stone facade reveals that this building was erected for the Mastan by Maharaj Tikamdas Lalmondas and his sons in memory of Mai Devi, widow of Visumalteumal. Constructed in 1910 with locally quarried limestone, thick masonry, and arched entrances, it stands as a testament to a period when Karachi’s public architecture reflected durability, civic purpose, and climate-responsive design. More than a century later, its fractured walls and shuttered doors tell a quieter story: one of slow erosion under Climate stress and prolonged neglect.

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which has repeatedly warned that South Asian cities face escalating risks from rising temperatures, humidity and extreme weather events. While floods and heatwaves dominate climate discourse, the IPCC notes that slow-onset impacts including material degradation and urban stress receive far less policy attention despite being largely irreversible.

In coastal cities such as Karachi, historic buildings face increasing exposure to rising temperatures, fluctuating humidity, saline air and irregular rainfall. According to UNESCO, these conditions accelerate processes such as salt crystallisation in stone, biological growth and mortar decay, particularly in heritage structures built with traditional materials. ICOMOS, the international advisory body on cultural heritage, has similarly warned that climate-driven moisture and temperature variability pose long-term threats to historic urban fabric in coastal regions.

Architect and urban planner Arif Hasan, who has extensively documented Karachi’s historic neighbourhoods, has observed that while many residents care about old buildings, serious conservation efforts and institutional respect for heritage remain largely absent. He notes that decay is magnified when maintenance systems fail and ownership is unclear. (Tribune Pakistan, 2022, link).

Ironically, many of Karachi’s older buildings represent models of climate-responsive design now being revisited by architects and planners. Research cited by UNESCO shows that traditional structures can maintain indoor temperatures four to six degrees Celsius cooler than modern concrete buildings, reducing dependence on mechanical cooling and lowering energy demand. Thick stone walls, shaded openings and natural ventilation once allowed communities to adapt to Karachi’s climate without electricity-driven solutions.

Despite this, Karachi continues to lose its architectural heritage at an alarming rate. In several cases, heritage experts have warned that once climate-related damage sets in, restoration becomes economically unviable.

The loss extends beyond aesthetics. UNESCO, in its reports on culture and sustainable development, has stressed that heritage buildings often serve as community anchors housing schools, low-income residents and social institutions. Their deterioration displaces communities, erases shared memory and removes climate-adapted spaces from neighbourhoods already facing environmental stress.

Globally, heritage preservation is increasingly framed as a matter of climate justice. UNESCO has warned that countries least responsible for climate change are losing cultural assets at the fastest rate, urging governments to integrate heritage protection into climate adaptation strategies rather than treating it as a standalone cultural issue.

For Karachi, experts argue that this requires policy integration rather than symbolic preservation, incorporating heritage protection into urban climate resilience plans, enforcing Sindh’s heritage legislation, allocating climate finance for conservation and adaptive reuse, and engaging local communities as custodians of historic spaces.

The 1910 building in the photograph still stands weathered, silent, but resilient. Its stone walls hold lessons in how cities once built with climate rather than against it. As environmental pressures intensify, preserving Karachi’s heritage is no longer a cultural luxury; it is a climate imperative, one that links memory, justice and sustainability in a rapidly changing world.